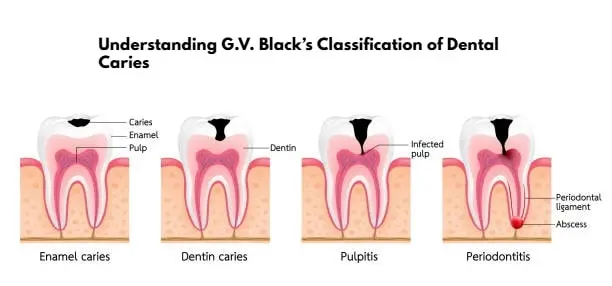

Imagine your tooth as a house with different rooms: the roof, the walls, the basement. If a leak springs up in one of those rooms, you send a different plumber than you might for the living room walls. Similarly, when you have tooth decay—also called dental caries—a dentist uses a system to tell exactly where the decay is so they know the best way to fix it. One of the most time‑tested systems in the United States is the classification developed by Dr. G.V. Black—often referred to as the “Understanding G.V. Black’s Classification of Dental Caries”

In this article, we’ll walk through what this classification means, why it matters in U.S. dental practice, a U.S.‑based case study + real‑world example, how you can remember the different categories, and some frequently asked questions. Whether you’re a dental patient, a parent, or simply curious about dentistry in the U.S., this guide will help you understand what your dentist means when they say “Class II” or “Class V” and how it affects your treatment.

What Is Understanding G.V. Black’s Classification of Dental Caries?

Dr. G.V. Black (1836‑1915) was an American dentist known as a pioneer of operative dentistry and dental education in the U.S. He created a classification system to describe cavities by location—that is, which surface of which tooth is decayed. The system has been used for more than a hundred years in American dental education and practice.In the U.S., dental hygienists and dentists learn this system early on because it gives a common “language” for describing cavities across professions.

Here are the classes described in simple terms:

Bullet point heading: Basic Classes (Location‑based)

- Class I – Decay in pits and fissures (grooves) of posterior teeth (molars, premolars), or on the lingual pit of upper front teeth (incisors).

- Class II – Decay on the proximal surfaces (the sides between teeth) of premolars and molars (back teeth).

Bullet point heading: Additional Classes

- Class III – Decay on the proximal surfaces of anterior (front) teeth (incisors and canines), without involving the incisal (biting) edge.

- Class IV – Like Class III but with involvement of the incisal edge of an anterior tooth.

- Class V – Decay on the cervical third (near the gum‑line) of the facial (cheek side) or lingual (tongue side) surfaces of any tooth.

- Class VI – Decay on the cusp tips or incisal edges of teeth. (This was added later to Dr. Black’s original scheme in many U.S. schools.)

This system helps U.S. dental professionals to quickly identify where the decay is and what kind of repair might be needed. It is widely taught in U.S. dental hygiene and dentistry programs for licensing and board preparation.

Why Is This Classification Useful in the U.S. Dental Practice?

In the U.S., dental care involves a team of professionals (dentists, hygienists, assistants) and often requires insurance documentation, treatment planning, and patient communication. The classification system developed by G.V. Black supports these in the following ways:

- Clear communication: When a dentist in, say, California or New York records “Class II lesion on tooth #14,” other team members know exactly what surface and what kind of restoration may be required.

- Treatment planning: Knowing the class helps the clinician anticipate how extensive the treatment should be. For example, a Class I cavity (in a groove) may be simpler and less costly than a Class III or IV which involves the biting edge or side between front teeth.

- Insurance & coding: The classification aligns with standard dental terminology used in U.S. insurance claims and dental records.

- Patient education: When dentists explain to patients “This is a Class V cavity near the gum‐line,” patients better understand why particular treatment or preventive steps are recommended.

- Education & training: It remains part of the curriculum for U.S. dental hygiene and dental students.

That said, there are limitations in U.S. practice as well: the classification focuses on location but not always on activity, depth, or risk of the cavity. Modern U.S. dentistry also uses other systems to measure lesion activity, severity, and minimal‑invasive approaches.

Case Study

Patient Profile

- Name: Lisa (age 14)

- Location: Austin, Texas, USA

- Complaint: Lisa complains of mild sensitivity when eating sweet foods, particularly in her upper right side back tooth (#3). Her dentist also notes a dark area on the chewing surface of the upper right first molar, which has visible grooves.

Diagnosis

The dentist finds decay in the pit and fissure of the occlusal (chewing) surface of the first molar (#3). According to G.V. Black’s classification, this is a Class I cavity (decay in pits/fissures of a posterior tooth).

Treatment & Outcome

- Treatment: The dentist removes the decayed portion, isolates the tooth, and places a tooth‐colored composite resin filling, ensuring the grooves are sealed and cleaned.

- Preventive follow‑up: Lisa’s dentist recommends applying sealants on other deep‑groove teeth (especially her second molars), improving her brushing technique (especially in molar grooves), and scheduling check‑ups every 6 months.

- Outcome: Within 12 months Lisa’s sensitivity is gone, no further decay develops in those surfaces, and the preventive steps help her avoid Class II or more complex lesions.

Why this matters

- The classification helped identify what kind of cavity it was (Class I) which guided a simpler, groove‐sealing strategy rather than a bigger repair.

- In the U.S. context, because Lisa is a teenager, early intervention prevented bigger future costs and treatment.

- The case shows how awareness of where cavities often begin (pits/fissures) leads to targeted prevention (sealants) in U.S. dental practice.

How to Remember the Classes

Here’s a simple way to memorize them—especially useful if you’re a student or you just want to understand your dentist’s explanations:

- House analogy:

- Roof = chewing surface grooves → Class I

- Walls between rooms = sides between teeth → Class II & III

- Front wall + big window = front teeth biting edge → Class IV

- Basement level near the foundation/gum line = Class V

- Chimney/top of roof/cusp tips = Class VI

- Or a phrase: “Grooves, sides, front sides, front edge, gum line, tips.” Map them to I, II, III, IV, V, VI.

Getting comfortable with the system lets patients understand what the dentist means and ask relevant questions: “You said it’s Class II—on tooth #14—so that’s the side between back teeth—what does that mean for me?”

Real‑World Example: U.S. Population Context

In the U.S., dental caries (tooth decay) remain one of the most common chronic diseases in children and adolescents. According to recent U.S. data:

- A study of children ages 0‑5 found about 67.5% had experienced decay.

- Racial and socioeconomic disparities persist: for example, in a North Carolina study, 39% of Black kindergarten students had decay compared to 30% of White students.

While these statistics do not refer directly to the class of cavities (Class I–VI), they underscore the importance of early detection, appropriate classification, and preventive measures in U.S. dental care.

Limitations & Modern U.S. Considerations

While the classification by G.V. Black remains very useful in U.S. dental education and practice, it has limitations:

- Focus on location: It tells where the decay is, but not always how deep it is or how active (growing) the lesion is. U.S. practices often include other systems or indices for severity, activity, and risk.

- Advanced minimal‑invasive strategies: In the U.S., dentistry increasingly uses minimally invasive treatments, preventive sealants, early detection of demineralization, and risk‐based care rather than only location‑based classifications.

- Root surface decay: The classification is less precise for root surface lesions or early non‑cavitated lesions (white spots) which are increasingly important in U.S. dental public health.

- Insurance & coding differences: U.S. insurance systems may require additional information beyond the class (for example, depth, pulp involvement) when coding and estimating treatment.

- Supplementary classifications: Many U.S. schools now teach systems such as ICDAS (International Caries Detection and Assessment System) alongside or after the traditional Black classification.

In short: the system is foundational, but modern U.S. dental practice uses it plus other tools for more complex, preventive, and risk‑based care.

Conclusion & Call to Action

Understanding the G.V. Black’s Classification of Dental Caries gives you a clear map of where tooth decay happens, why it matters, and how dentists decide on treatment in U.S. dental practice. When you know where the damage is, you’re better equipped to ask smart questions, take preventive steps, and engage more confidently in your dental care.

If you have a dental appointment coming up in the U.S., ask your dentist: “What class is my cavity, and what does that mean?” And if you have children, use the knowledge of these classes to guide their check‑ups: look at the chewing grooves (Class I), sides between teeth (Class II/III), near the gum‑line (Class V) and so on. Prevention is easier when we know where to look.

If you like, I can help you find a U.S.‑based printable guide or flyer you can use at home (for yourself or your kids) to spot these surfaces and ask the right questions at your next dental visit. Would you like me to find that?

Understanding G.V. Black’s Classification of Dental Caries

FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

- Does the classification system apply to baby teeth (primary teeth) in the U.S.?

Yes—while Dr. Black’s system was developed for permanent teeth, U.S. dentists often use the same location‑based logic when working on primary (baby) teeth, though treatment decisions may differ because of age, eruption status, and lifespan of the tooth. - If my dentist says “Class II” on a back tooth, does that mean a bigger or more expensive filling?

Not necessarily more expensive, but often more complex than a simple groove filling. Because a Class II lesion is between teeth (proximal surfaces) of premolars or molars, the dentist has to consider access, contact points, and restoration of the side surface—not just the top. That can sometimes mean slightly more time, technique, and cost. - Can a cavity change from one class to another over time?

The classification refers to where the cavity is currently located, so it doesn’t “change class” per se. However, decay can spread into other surfaces or edges, creating a new lesion in a different class. For instance, a groove cavity (Class I) might extend into a side contact area and become Class II in effect if left untreated. - Is this classification system taught in U.S. dental hygiene programs and used for licensing exams?

Yes. U.S. dental hygiene and dentistry schools consider the G.V. Black classification “must‑know” content, and it appears in national board exams and licensing preparation. - As a patient in the U.S., how does knowing the class help me?

Knowing the class helps you understand the location of the cavity and ask relevant questions, like: “How accessible is this surface for cleaning?” “Does this location need a sealant or special care?” “What’s the risk of it getting worse?” It empowers you to be part of the discussion with your dentist about prevention, cost, and treatment.

Must‑Know Classifications of Dental Caries for the National Dental Hygiene Boards – DentistryIQ